- Home

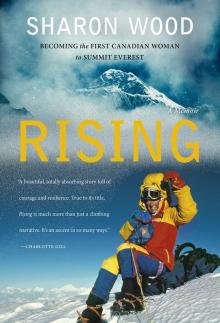

- Sharon Wood

Rising

Rising Read online

Rising

Sharon Wood

Rising

Becoming the First Canadian Woman to Summit Everest, A Memoir

Copyright © 2019 Sharon Wood

First editions published simultaneously in 2019 in Canada by Douglas and McIntyre (2013) Ltd. and in the United States of America by Mountaineers Books.

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system or transmitted, in any form or by any means, without prior permission of the publisher or, in the case of photocopying or other reprographic copying, a licence from Access Copyright, www.accesscopyright.ca, 1-800-893-5777, [email protected].

Douglas and McIntyre (2013) Ltd.

P.O. Box 219, Madeira Park, BC, V0N 2H0

www.douglas-mcintyre.com

All Everest Light expedition photographs, with or without credits, were taken by expedition members with cameras provided by Leica.

Quote on page vi: From LETTERS TO A YOUNG POET by Rainer Maria Rilke, translated by M. D. Herter Norton. Copyright 1934, 1954 by W. W. Norton & Company, Inc., renewed © 1962, 1982 by M. D. Herter Norton. Used by permission of W. W. Norton & Company, Inc.

Part 1 quote on page 1: adapted from Barbara La Fontaine. “Scared of Bears and Scared of Being Scared,” Sports Illustrated, July 18, 1966, 51.

Part 2 quote on page 173: Excerpt from KAFKA ON THE SHORE by Haruki Murakami, translated by Philip Gabriel, translation copyright © 2005 by Haruki Murakami. Used by permission of Alfred A. Knopf, an imprint of the Knopf Doubleday Publishing Group, a division of Penguin Random House LLC. All rights reserved. Copyright © 2005 by Haruki Murakami. Reprinted by permission of ICM Partners.

Edited by Lucy Kenward

Dust Jacket design by Anna Comfort O’Keeffe and Carleton Wilson

Text design by Carleton Wilson

Printed and bound in Canada

Printed on paper certified by the Forest Stewardship Council

Douglas and McIntyre (2013) Ltd. acknowledges the support of the Canada Council for the Arts, which last year invested $153 million to bring the arts to Canadians throughout the country.

Nous remercions le Conseil des arts du Canada de son soutien. L’an dernier, le Conseil a investi 153 millions de dollars pour mettre de l’art dans la vie des Canadiennes et des Canadiens de tout le pays.

We also gratefully acknowledge financial support from the Government of Canada and from the Province of British Columbia through the BC Arts Council and the Book Publishing Tax Credit.

Library and Archives Canada Cataloguing in Publication

Title: Rising : becoming the first Canadian woman to summit Everest : a memoir / Sharon Wood.

Names: Wood, Sharon A., 1957- author.

Identifiers: Canadiana (print) 20190114525 | Canadiana (ebook) 2019011455X | ISBN 9781771622257

(hardcover) | ISBN 9781771622264 (HTML)

Subjects: LCSH: Wood, Sharon A., 1957- | LCSH: Women mountaineers—Canada—Biography. | LCSH: Mountaineers—Canada—Biography. | LCSH: Mountaineering—Everest, Mount (China and Nepal) | LCSH: Everest, Mount (China and Nepal)

Classification: LCC GV199.92.W66 A3 2019 | DDC 796.522092—dc23

For my boys.

…I want to beg you, as much as I can, dear sir, to be patient toward all that is unsolved in your heart and to try to love the questions themselves like locked rooms and like books that are written in a very foreign tongue. Do not now seek the answers, which cannot be given you because you would not be able to live them. And the point is, to live everything. Live the questions now. Perhaps you will then gradually, without noticing it, live along some distant day into the answer. —Rainer Maria Rilke, Letters to a Young Poet

Contents

Preface ix

Part 1 Chapter 1: The Promise 3

Chapter 2: Neighbours 13

Chapter 3: Friends, Nomads and Spirits 19

Chapter 4: Rescue 29

Chapter 5: Weight 37

Chapter 6: The Power of Story 47

Chapter 7: Redemption 57

Chapter 8: One Hundred Trips 65

Chapter 9: Proving Grounds 77

Chapter 10: Mentors and Muses 87

Chapter 11: Shit, Grit and Yin 97

Chapter 12: Ya Gotta Want It! 107

Chapter 13: Small Plans 115

Chapter 14: The Meeting 127

Chapter 15: Glory or Death 139

Chapter 16: Commitment 145

Chapter 17: Summit Day 163

Part 2 Chapter 18: Into the Dark 175

Chapter 19: Coming Down 179

Chapter 20: Lost 189

Chapter 21: On Stage, Off Stage 197

Chapter 22: Reunion 217

Acknowledgements 227

Photos I

Preface

Throughout the process of writing this book I have been asked, “Why now, after all this time?” Becoming the first North American woman to summit Mount Everest catapulted me into an accidental career as an inspirational speaker for three decades. Although my climbing has had an impact on who I am, I never expected this one climb to permeate my life to the extent it has. Not a day has gone by without some reference to Everest, whether from a friend or a stranger; from a journalist, a student or a speakers’ bureau; or from an aspiring mountaineer or an autograph hound. I have been surprised and sometimes dismayed to discover Everest is not going away.

Everest has opened doors for me and expanded my world. But at times, Everest has felt like an overbearing friend. It has often preceded me, elbowed its way into rooms, sashayed across floors, cut swaths through conversations and embarrassed me. Outside of my work as an inspirational speaker, I have been quiet about this particular mountain. Some friends have accused me of being coy when I do not let Everest speak for me, but this is how it is: complicated.

When people in my audiences asked when I was going to write a book, I would tell them: “When I’m old and wise enough.” And I would tell myself: never. However, much has changed. Access to Mount Everest has increased exponentially. Still, despite the mountain having been desecrated by commercialism, reality TV, garbage, and sometimes, questionable motives, a fascination with this icon of human achievement has endured. I’ve had more than thirty years to ponder why some folks can’t hear enough about it. Climbing Everest reveals the best and the worst of the human condition. The story I have told to over a thousand audiences conveys the former: a story of exceptional teamwork and the impact it has had on my life.

My realization that Everest was going to remain both a part of my life and the public consciousness coincided with my children leaving home and resuming my original career as an alpine guide. Returning to my guiding work was a relief and a comfort. I realized how much I love to show others the elegance of moving over rock, snow and ice. More fulfilling than teaching specific skills, however, is helping people find themselves in the mountains. By showing others, I reminded myself that the mountains are a powerful teacher. All these factors inspired me to delve deeper into the story I usually tell audiences in less than an hour.

As overbearing friends can be, Everest wanted this book to be about it. But the mountain merely serves as a stage and a timeline for the real story. I did not know this until now. I had to write this story to “live the questions” and discover that the most important thing Everest has taught me is the value of relationships: my relationship with myself, with some remarkable people and with the world around me.

I have had to answer for my motives many times during this writing process. Who am I to talk about myself? I had considered this indulgence an unwholesome luxury until I realized one

of the reasons I read memoir is to know I am not alone.

I have taken advantage of the liberal rules for non-fiction narrative to inhabit the young woman I was then, when the events were newborn, and I, less aware. I have recreated scenes and conversations to convey the events, the character of myself, my teammates and friends, and our relationships, to the best of my recollection. This story has been with me long enough to make me wonder whether I had it straight, especially after retelling it for so long. To this end, I asked a few teammates to read the manuscript to make sure events lined up with the facts.

My teammates have also helped me with several questions: How did we succeed on the seldom-climbed West Ridge of Everest when so many had failed? Eight men before us had died on this route out of a total of thirteen who had attempted it. And why was it that only two of us out of all the talented climbers on our team reached the summit? Then, why me? And perhaps the most vexing question: Why did I struggle with my Everest acclaim?

A buffer of three decades has given me the courage to expose both my frailties and my motivations, and allowed for admissions that I would not have had the insight or courage to disclose when I was younger. The years have seasoned my perspective and softened some edges. I squirmed with discomfort as I wrote into such self-centred focus and how seriously I took myself then. I passed the manuscript to more readers, this time to make sure I was accurately depicting myself. One friend told me he believes we could not have achieved what we did in our twenties without having taken ourselves so seriously. We were compelled to strive and put ourselves first when it came to realizing our capacities and who we were in this world. But to what end? This is another question I have wrestled with since my time on Everest, giving me both cause to cringe in shame, and fodder for growth and insight.

The questions, I realize now, are more important than the answers. After having raised two high-spirited boys I understand this. All I’ve ever wished for them, beyond good health and love, are challenges and questions that engage and compel them. As ambivalent as I may sound about Everest, I am grateful for how it has continued to challenge me even more so in writing this book.

So here we are. I had to rise to climb Everest, and rise to integrate that experience into my life. This need to engage in the questions is the irrepressible engine for writing my story.

Part 1

There is more in us than we know. If we can be made to see it, perhaps for the rest of our lives, we will be unwilling to settle for less. —Outward Bound

Chapter 1

The Promise

March 17, 1986

With movement comes comfort. In the dark, between Laurie and Jim, mentor and leader, I doze as my head jounces and lolls between their shoulders. We are nestled in the cab of a five-ton diesel truck climbing via sixty or more switchbacks to reach Pang La, a 5,200-metre-high pass on the Tibetan Plateau.

While the rest of our entourage overnights in Shigatse, we are getting a head start with the slower-moving truck carrying our cargo. The truck heaves and sways over potholes and then races toward the next straightaway, pressing our spines into our seatbacks. At first we braced ourselves, our hands on the dashboard or the roof, careful to not touch one another in the jostle. But now we’ve surrendered to the movement and relax into each other. Rather than try to talk over the truck’s throaty growls and sighs, I stare through the sandblasted windshield. It feels like no one else is awake in the world.

A scent—part feral, part mothballs—fills the cab. Rawhide and thongs wrap the driver’s ankles, replacing the missing eyelets and laces in his boots. Bailing wire binds the rest of the boot to the sole. He wears a khaki green cap with turned-up fur-lined earflaps and a parka and pants with a time-worn sheen at the elbows and knees. I guess his clothing is Chinese People’s Liberation Army cast-offs, and he, Tibetan. His face is all sharp angles. There is some fire in his eyes—a hint of hope that it’s not over yet for his beleaguered country the Chinese now occupy. He has offered no name, nor answers to our questions, and I wonder if it’s because he doesn’t understand or if he’s been ordered to remain silent. Soon, my eyes close and I feel myself being rocked and cradled as we rise.

I wake with a start when Jim slaps his palm on the dash. “Stop here!” he says. He raises his arm and slices the air. “Cut!” The driver pumps the brake and wrenches the emergency lever up and the truck comes to a stop. Then Jim points at us, the roof and the back of the truck. “We ride up on back.”

Laurie yanks the door lever up and pushes his shoulder into the door. It creaks open and he steps down, then offers me his hand. In the dim of the pre-dawn light, the three of us stumble around to the back. We climb over our cargo and wedge ourselves so we can look out over the cab. Jim slams his hand on the roof and yells, “Okay, go!”

With the drawstrings of our hoods cinched tight around our faces, we huddle close to fend off a cold wind that bites through our clothing. Laurie pulls me into his side as he shouts over the din of the truck and the rush of the wind, “Any minute now!”

Jim reaches across my back and grips my shoulder. He points. “Here it comes, Woody!”

As we crest the top of the pass at sunrise, Laurie sweeps his arm over an ocean of brown hills crowned by the white wall of the Himalayas in the distance, and says, “Sharon Wood, welcome to Mount Everest!”

The driver pulls over to stop amidst rows of rock cairns festooned with string upon string of prayer flags streaming in the wind. Far off, the mountain that I’ve been planning for, thinking about, dreaming about, reigns above all else on the horizon, with a plume of snow tearing off its top. But what hits me harder than this first sight of Everest is how grateful I am to be sharing this experience with these men who have been so instrumental in bringing me to this magical moment. There’s no one in the world I’d rather have beside me, and I sense I’ll feel this way every day for the next two and a half months of my life.

We travel for several more hours before reuniting with our ten other team members, and our Chinese Mountaineering Association liaison, interpreter and their cook at the entrance of the Rongbuk Valley. Travelling in faster jeeps, they have caught up to us at this gateway to Everest, or Chomolungma, as it is known to the Tibetans.

Raging monsoon waters and extreme melt–freeze cycles obliterate the final stretch of the road to Basecamp every year. This year seems no exception and I am thinking we will have to walk the last three kilometres.

A straggle of Tibetans huddles in the lee of an abandoned stone hut. They are all sinew and tendon, with weather-beaten faces, and clad in a contrast of second-hand ski jackets, hide and homespun. We wait in the jeeps and watch our Chinese interpreter, Mr. Yu, inch open his door against the pressing wind to speak to them. His cap flies off his head and a Tibetan’s arm darts out and snatches it mid-flight. Mr. Yu totters with arms out as he picks his way over the rubble toward the man. The Tibetan meets Mr. Yu with a bow and a thin smile as he returns his cap.

Mr. Yu and the men talk as they point upvalley. Then the Tibetans shoulder pry bars, shovels and pickaxes and make their way to the head of the cavalcade. As we start moving, some trot easily beside us while others ride the jeeps’ bumpers like broncos, their bodies folding and rocking to the buck and jostle. When we roll to a stop at the edge of a torrent, they stride ahead through the hip-deep rushing water and leap up onto the ice-bound rock shelf on the other side. Some chop away at its edge while others pry boulders and shovel gravel. Soon, there is a ramp leading up the opposite bank. The labourers wade back toward us, their clothes wicking water up past their chests as they rearrange rocks they have rolled into the river for the vehicles to drive on.

It will take the dozen or so men a few hours to prepare the final stretch to Basecamp. While we sit warm and dry on soft, cushioned seats, their hardship, and our comfort, keeps my eyes from meeting theirs. We are climbers here for good reason, not tourists, I tell myself. But I recognize the Tibetan man’s th

in smile to Mr. Yu as one for us all.

* * *

By mid-afternoon, we unfold from jeeps and trucks, stiff from three days’ travel on rough roads from Lhasa. Dazed and light-headed from the thin air, we take measure of our new home. I match landscape to images seen only on paper until now. Everest sits at the head of the valley, fifteen kilometres away. From where we stand the only sign that ice once filled this kilometre-wide valley are terminal moraines—piles of rocks and boulders thirty metres high that mark the end of the glacier’s path and the beginning of ours.

It is a clear day, perhaps just above freezing, but I feel chilled. There is spite in this wind that rips at our clothing and pushes and shoves us. Gusts drive silt into our eyes and our layers. By day’s end, that grit will have found its way right down to my underpants. Driven by instinct to make shelter before nightfall, we don more clothing and shift from pause to rush as we set to task.

Jim and Jane, our cook, trundle off to stake out a location for the mess tent. Their balance and reaction time, like mine, are off and they stumble like drunkards. The new altitude of approximately 5,200 metres above sea level is equivalent to a half atmosphere. Even though my heart bounds and my lungs fill and empty like a bellows to compensate, I can’t get enough oxygen to fuel the simplest functions.

Barry and Kevin pass off loads from atop the trucks as the others grapple with the slippery boxes and plastic barrels. Shoulder to shoulder, Dwayne and I huddle over the records of inventory we packed six months ago. The wind snatches at the papers on our clipboard while I hold them down with both hands, and Dwayne checks off items as they hit the ground. We scramble to meet the volley of demands for tents, pots, food and tools. Dr. Bob, our team doctor, squints through dust-caked glasses as he points bearers to piles. If arranged end to end, the five tonnes of food and equipment—150 boxes, barrels and duffle bags—could span the length of a football field.

Rising

Rising